The Struggle of a Plant Pathologist in Papua New Guinea

Dr. Toshiro Shigaki, our technical advisor, and Mr. Kanayama, President of Nippon Gene, held a dialogue. Looking back on the time when our products were used in Papua New Guinea, we talked about the problems of plant diseases and the challenges ahead, as well as international cooperation.

Through the discussion, we would like to consider our role and the way we should be in order to continue to grow sustainably in the international community.

Interviewer:Shinji Kanayama

President of Nippon Gene

Interviewee:Toshiro Shigaki

Director, Pacific Agriculture Alliance

Specially Appointed Researcher, The University of Tokyo

Advisor to the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock, Solomon Islands

Technical advisor of Nippon Gene

Kanayama

Kanayama

Hello, today I’d like to talk to Dr. Shigaki, who has a variety of overseas experiences and is also our technical advisor. Dr. Shigaki introduced our phytoplasma detection kit in Papua New Guinea in 2017. We’d like to ask him about the story at that time.

Due to the coronavirus′s influences, it is recommended to avoid traveling as much as possible, so we decided to have this interview online. Dr. Shigaki, thank you for your time today.

Thank you for taking the time.

Shigaki

Shigaki

Kanayama

Kanayama

At first, I would like to introduce brief background of Dr. Shigaki. Dr. Shigaki did a research fellowship at Baylor College of Medicine in Texas, USA, after receiving a degree from the University of Hawaii, USA. He was a senior researcher at the National Institute of Agricultural Research in Papua New Guinea and a visiting professor at the Indian Institute of Advanced Science, and is currently the president of the Pacific Agricultural Alliance.

At the same time, he is also a special researcher at the University of Tokyo and an adviser to the Solomon Islands Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock.

So, first of all, could you tell us what kind of research you were doing in the United States and why you decided to get a degree abroad?

| 1996 | Graduated from the University of Hawaii (Ph.D. in Plant Pathology) |

| 1996 | Postdoctoral Fellow of Samuel Roberts Noble Foundation, Oklahoma, USA (~1999) |

| 1999 | Researcher of Baylor College of Medicine (~2010) |

| 2007 | Invited professor of Indian Institute of Advanced Research |

| 2010 | Principal investigator of plant pathology, Papua New Guinea National Agricultural Research Institute (~2016) |

| 2016 | Director, Pacific Agriculture Alliance (~now) Specially Appointed Researcher, The University of Tokyo Advisor to the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock, Solomon Islands |

Thank you for the introduction. In the U.S., I got my M.S. and Ph.D. degrees in plant pathology, but after that, I was also involved in fields such as plant physiology and molecular biology. Especially at Baylor College of Medicine, I was trying to create a so-called designer protein that could change the specificity of the transport proteins of metal ions using an original gene-modification technology. This was a bit out of the scope of our laboratory’s research, so at first my boss was not very happy about it, but when the results came out, it became the main theme of the laboratory.

I came from the University of Toyama and majored in physics, but I took advantage of my free time to ask Professor Anayama’s laboratory in the Faculty of Education to let me take a special class in agriculture. The Physics Education Department in the university asked me a lot about the reason when I registered for the course, but I think I managed to get more than 10 credits in total.

After that, I worked as a teacher for about five years in Okazaki, Aichi Prefecture, but I always wanted to do agriculture. I learned that you can learn whatever you want at a graduate school in the U.S., no matter what your undergraduate major is. Therefore, I decided to go to the United States.

I needed to study English, but it was difficult to do so when I was working as a teacher, so I quit the job after 5 years of working and decided to work at a cram school in Nagoya because I could use my morning hours to study English. I had set a goal of scoring 650 points on TOEFL, which I immediately achieved, but I actually ended up working at the cram school for more than four years because I found it interesting so much. It may have been a bit of a mistake.

But when I was reading the newspaper at just the right time, I found out about a program (Allex Scholarship) that offered free tuition and living expenses for graduate school if I taught Japanese in the U.S. I applied for it and was very lucky to be accepted. I was the second recipient of that Allex Scholarship.

Shigaki

Shigaki

Kanayama

Kanayama

Thank you. I understand that you have experienced a lot. After that, you worked at the National Agricultural Research Institute of Papua New Guinea, and this was where the relationship with our company arose, but Papua New Guinea is a country that is not familiar to Japanese people, I think. Why did you decide to work in Papua New Guinea?

I actually chose the country of Papua New Guinea by accident. I decided to leave the U.S. due to my wife’s difficulty in getting an American visa. Actually I needed to find a job right away, and I happened to mention this to an Indian graduate student that I was teaching. He was from a prestigious Indian Institute of technology (IIT), which has a network of alumni all over the world. He worked hard for me, and then he found out that the National Institute of Agricultural Research in Papua New Guinea seemed to be accepting me. They found it for me really quickly, and I thought IIT’s network is really awesome.

So it was really a coincidence that I started working in Papua New Guinea. But even though it was a coincidence, I loved Papua New Guinea, it was a three years contract but I renewed it once more, and I ended up living there for six years. I had been doing molecular biology research in the lab for a long time, and I was a little bit away from field research on plant pathology. One of the main reasons why I liked Papua New Guinea was that I was able to see actual plant diseases in the field.

Shigaki

Shigaki

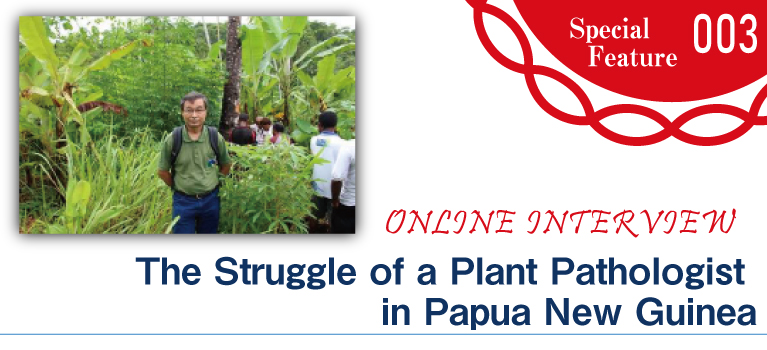

Left) Location of Japan and Papua New Guinea. It is located almost south of Japan near the equator and a little north of Australia (This map is based on the Digital Map published by The Geospatial Information Authority of Japan)

Right) The flag of Papua New Guinea. It depicts the Southern Cross and the national bird, the red-crowned crane.

Urban (Left) and suburban (Right) area of Papua New Guinea.

Kanayama

Kanayama

You were introduced to Papua New Guinea by an Indian student who was taught by you. I am not very familiar with Papua New Guinea, so could you please explain briefly what kind of country it is?

Yes. There was a TV show to introduce some fascinating countries a long time ago, and I remember the story about visiting the indigenous people in the jungles of Papua New Guinea, so I was very excited about it even before I was assigned to the post.

But my boss at Baylor College of Medicine did not look too good and said sarcastically, “You think you can do scientific research in a place like Papua New Guinea?” I didn’t mind though.

When I went there, I was really impressed because it was just like a TV show I used to watch. Everywhere I went, the river water was crystal clear and clean, and the whole country seemed to be covered in jungle greenery. And I was very impressed by the taste of the fruits and vegetables. Pineapples, for example, are really sweet to the core. If I leave the stalks of the pineapples in the garden after I eat, they will grow back after about 2 years, which is quite useful. If I leave the seeds scattered in the garden after eating the papaya, they will soon grow on their own. So, there is no shortage of fruit. I also had other trees in my house, like coconut and mango trees.

Shigaki

Shigaki

Pineapples from the market. It is sweet and tasty not only it’s body but also the core.

Although it is a tropical country, the largest population is actually in the highlands, where the weather is very cool. There are several branches of the National Agricultural Research Institute in the highlands, and when I went there on a business trip sometimes, I remember that there were a fireplace in the lodgings and it was very cold in winter. You may be surprised to hear that.

Shigaki

Shigaki

A traditional Papua New Guinea house (Left) and the house where I lived at the time (Right). The house is built on stilts to prevent water and insects from entering the house.

Some guesthouses in high altitude areas have indoor fireplaces.

Boats with engines are an important means of transportation in the coastal areas. Fishing is also done by canoe.

Kanayama

Kanayama

Okay. Concerning the National Institute of Agriculture Research which you mentioned earlier, what kind of work did you do there?

Yes, the headquarters of the National Agricultural Research Institute was located on the outskirts of the city of Lae, the second largest city in Papua New Guinea where there is a large concentration of factories and a large port.

Shigaki

Shigaki

Lae is located to the north of Port Moresby, the capital city. In the photo right is the National Agricultural Research Institute where I worked at the time, located in the suburbs of Lae.

In 2010, when I was appointed to the position, there was a project to build a biotechnology center, and I was involved in the design of the center from the beginning. When it was completed in 2012, I was given a very nice office, but the labs were empty, and we didn’t have much of a budget. Even so, I happened to be able to obtain EU research funding, about 100 million yen in total, and with that money we were able to buy basic equipment such as a thermal cycler, a -80°C freezer, and a gel imaging system, so we were able to conduct very basic experiments.

The EU project is to do the research on sweet potatoes which are one of the local staple foods, and a leafy vegetable called Aibika. We also did quite advanced things for Papua New Guinea with the cooperation of RIKEN in Japan, such as using heavy ion beams to mutate and improve breeds.

Shigaki

Shigaki

Aibika. Locally, it is used in stews and other dishes.

There is a place called Bougainville Island, where sago palm tree, a very important for the island, was almost wiped out by an unknown disease. As well as finding out the cause of the disease, we started a project to plant trees that are resistant to the disease. This project has been ongoing after returning to Japan.

I was also very interested in the protection of plant genetic resources, so I was able to help Papua New Guinea ratify the ITPGRFA, an international treaty that established rules for the use of seed genetic resources. As the first representative of that country, I was nervous to speak at the big meeting at FAO headquarters in Rome, but it was a unique experience.

Shigaki

Shigaki

Dr. Shigaki attending a meeting held at FAO headquarters as a representative of Papua New Guinea.

When there was a plant disease in Papua New Guinea, I received the report about the plant diseases in first place, which I was very grateful for, because the initial countermeasures are very important. Now thanks to Nippon Gene, I am able to attend a plant protection conference in the Philippines every year, and I am very pleased to obtain the information on plant diseases in Southeast Asia.

The most important plant disease in Papua New Guinea was a coconut phytoplasma disease called Bogia coconut syndrome (BCS), which occurred in a northern province called Mandang. I will explain this later.

Shigaki

Shigaki

Kanayama

Kanayama

You adopted our kit for the coconut phytoplasma disease that you just mentioned, but did you already know about our company?

In the Madang area where the Bogia Coconut Syndrome (BCS) occurred, there was a gene bank of coconut palms from the South Pacific, and the disease had spread very close to the bank, so we decided to move the gene bank to another location before the bank got contaminated. We needed to test the coconut palms for phytoplasma infection before transferring them, but we could not do PCR because the local laboratory facilities were not sufficient.

Shigaki

Shigaki

A healthy coconut palm (Left) and a dead coconut palm infected with phytoplasma disease (Right).

I checked the literature and found that there was a very good antiserum in Professor Namba’s lab at Tokyo University, Japan. When I contacted Dr. Namba, he replied that the LAMP method was better than serological method. He told me that the company making the LAMP test kit was Nippon Gene. As I introduced earlier, I was from the University of Toyama, so I felt a strong attachment to the company from the beginning.

Shigaki

Shigaki

Entering the jungle and drilling the trunk of a coconut palm to collect specimens.

Kanayama

Kanayama

Thanks to your help, we were able to have our kit used in Papua New Guinea but at that time you held a handover ceremony for the local government, didn’t you? What was the handover ceremony like?

Phytoplasma’s LAMP kit was developed at the request of the CCI (Papua New Guinea Cocoa and Coconut Research Institute), which manages the coconut gene bank. Thanks to Nippon Gene and the professors at the University of Tokyo, we were able to make a very good kit. So, to promote it externally, we decided to hold a handover ceremony of the kit.

From Nippon gene, President Yoneda (at the time) came from Toyama, Japan, and also had the Minister of Agriculture and local government officials from Papua New Guinea, as well as JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency) officials from Port Moresby, the capital city of Papua New Guinea, in attendance. It was quite a big ceremony. The ceremony was covered on TV and became a hot topic in the region. At the handover ceremony, several people who participated in the handover ceremony asked us to develop a kit that could be stored at room temperature because it was difficult to transport and store the kits in frozen form in Papua New Guinea. This led to the development of a dry-type kit.

Shigaki

Shigaki

A researcher (Right) explaining the LAMP kit for phytoplasma in the lab, and senior government official (Left) listening to it. It was covered by the local media.

Kanayama

Kanayama

You mentioned the transportation and storage, but is there an environment in Papua New Guinea where this kind of plant disease can be tested?

I think there were only a few places where PCR could be performed in the whole of Papua New Guinea, including the National Agricultural Research Institute where I worked. The electricity supply is very unstable, so if a lab does not have a generator, it is impossible to freeze or refrigerate chemicals. Even if a facility has such equipment, chemicals are imported from foreign countries and it takes a very long time to import them. Sometimes they may be kept at the airport because of the procedures at the airport. In such a case, the very expensive reagents that we had bought were often useless due to long-term storage under high temperature.

In that respect, LAMP dry-type kit does not have such concerns. Also, the fact that we can take it anywhere regardless of temperature is very convenient for the local people. At the handover ceremony, president Yoneda went to a remote village to inspect the phytoplasma infected plants to show the local people how easy it is to use the kit without any special equipment. It was a great surprise to see the results using water boiled in a pot placed in the field instead of a thermostatic chamber.

Shigaki

Shigaki

We went to a village where the phytoplasma disease was spreading and prepared a thermostatic condition for testing by boiling water over a fire.

Village children were curious about the inspection and president Yoneda (at that time) looked up at a local coconut tree.

Kanayama

Kanayama

Well, I see that our kits could be used even in areas where infrastructure is not in place. Phytoplasma kits are now being asked for from all over the world, not just in the Pacific states, so I feel the threat of this disease. Is it difficult to prevent plant diseases like this, not just phytoplasma?

In my opinion, the incidence of various new plant diseases seems to be much higher than before. This may be due to the effect of climate change. The demand for testing is also increasing along with it, and I think LAMP is a wonderful technology from Japan that can meet this demand.

As with coronaviruses, once a plant disease has spread, it becomes very difficult to deal with. It is important to establish a system that enables early detection of plant diseases. This may be done through quarantine, and also it is important for the farmers to have an discerning eye on the site. When those people find a suspicious plant, it is important for them to have the tools to examine it immediately and to use the tools correctly.

Shigaki

Shigaki

Kanayama

Kanayama

I understand. Is there any other plant disease that has become a problem in the world?

Phytoplasma is a very troublesome disease because it is a problem in many countries but difficult to test. Other plant disease emergencies are occurring in many parts of the world. For example, recently, a disease called wheat blast has been spreading in Asia, which is staple food for wheat along with rice. The disease first appeared in South America in the 1980s, but it spread to Bangladesh in 2016 and then to India in 2017 causing significant damage.

My biggest concern right now is a disease called the new Panama disease of bananas. The Cavendish variety of banana which we are currently eating is very susceptible to a strain of the fungus Fusarium TR4 (Tropical Race 4). The disease is spreading in the Philippines and other parts of the world, and it has also spread to India, which is the world’s largest producer of bananas, and is said to be a coronavirus on bananas. Diseases of bananas caused by TR4 are difficult to distinguish from those caused by other pathogens, therefore accurate diagnosis is important for countermeasures.

Shigaki

Shigaki

Kanayama

Kanayama

We feel that it is very important to prevent the spread of plant disease as they can lead to food problems. Our company addresses this issue by providing test kits for plant diseases. On the other hand, you run your own corporation and you are working on this kind of agricultural problem. What kind of activities are you doing?

The Pacific Agriculture Alliance, which I am the director of, is currently working on a project to revive sago palms on Papua New Guinea’s Bougainville Island. About 30 years ago, sago palms, an important resource on the island, were killed one after another by a disease that was thought to be caused by a fungus. By 2010, all sago palms were nearly wiped out.

Shigaki

Shigaki

Sago palm tree. It stores starch in its trunk.

The project is to select disease-resistant sago palms and plant their seedlings all over the island. We have been working on this project for about seven years now, and it has been very successful with supportive helps from the islanders and the local government of Bougainville.

My dream is to see Bougainville Island covered in sago palms as it used to be. It will take at least another 15 years or so.

Shigaki

Shigaki

The workshop at the Sago Palm Project.

Also from August of this year, we were also planning to start a project with JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency) for early detection of plant diseases in the Solomon Islands in the east of Papua New Guinea, but this is likely to be postponed due to the coronavirus. (*As of July 2020, the decision has been made to postpone officially). I will also coorperate with Nippon Gene on this project. I am hoping to start this project soon.

I would also like to do something about the new Panama disease in India and Philippines, which I mentioned earlier. Ultimately the best solution is to develop bananas that are resistant to TR4 and taste good, but we need the original banana varieties to accomplish it. Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands are a treasure trove of genetic resources, so I would like to focus our efforts on the protection of these plant genetic resources as well.

Shigaki

Shigaki

Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands are very rich in genetic resources including bananas. The protection of genetic resources leads to the conservation of biodiversity.

Kanayama

Kanayama

Thank you very much. Nippon Gene also hopes to grow while contributing to society by working on social issues, especially those related to health and food, using our proprietary biotechnology. The development of technologies and products to solve problems is the engine of our growth.

Today’s talk by Dr. Shigaki, I could feel his strong passion in spite of his gentle tone. Our company also would like to work on the world’s plant disease problems with passion.

Thank you very much for today.

Thank you very much, too.

Shigaki

Shigaki

*Photo courtesy: Toshiro Shigaki